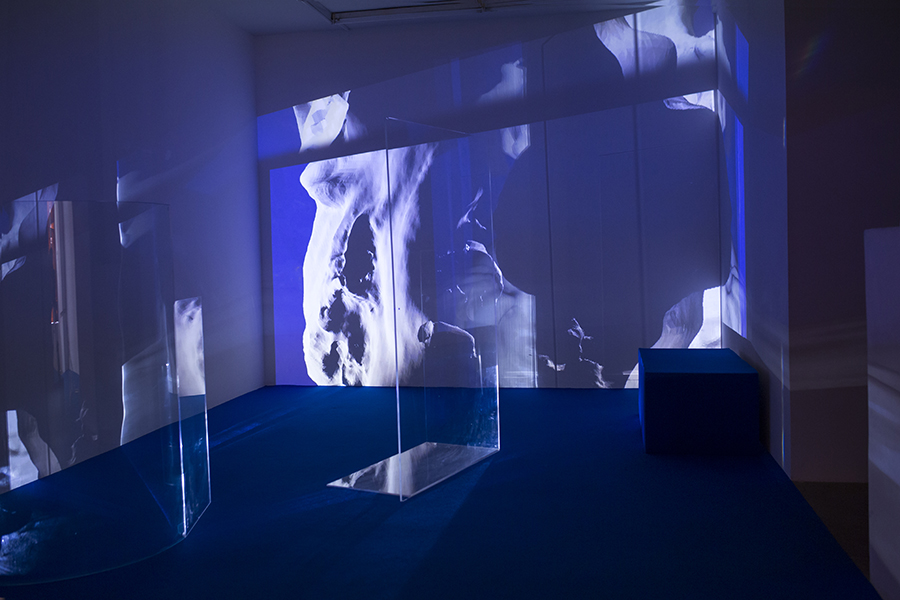

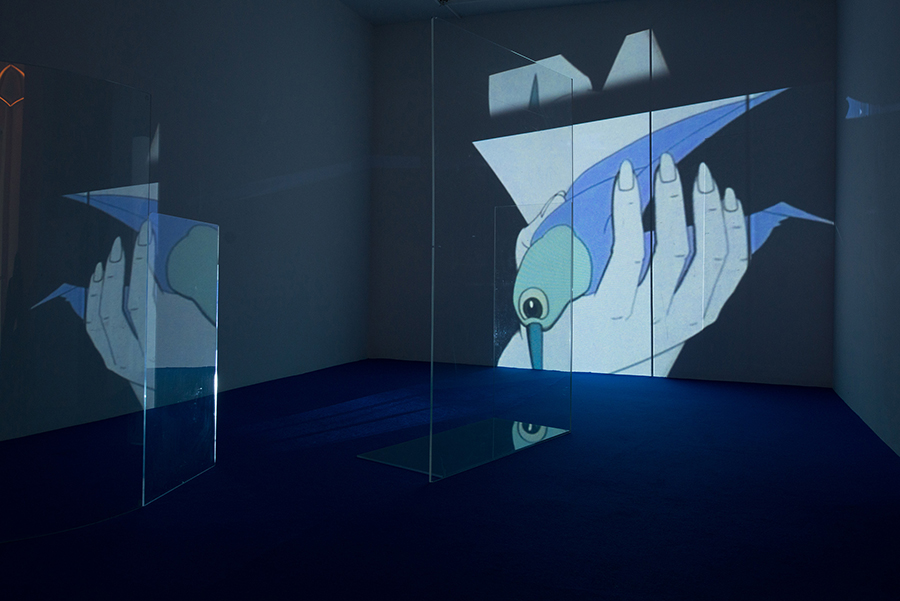

In the video installation which gave its title to the exhibition (physical self 2017) and takes place in the second room of the gallery, analogue and digital images as well as movie and scientific images are all chained together in un-symmetrical frames. The images go through a multiplication and refraction device perfectly mastered by Laura Gozlan. The device is made of Plexiglas and glass surfaces (the curved one is glass) located between the projector and the back wall used as a screen. Although the surfaces are see-through and enable the projected beams of light to go through them, they do possess an opacity that heightens their plasticity.

Amongst the images flow, one can identify extracts from the Japanese anime Perfect Blue (1997) by Satoshi Kon, but also a 3D model of the artist’s torso and facial movements. The camera follows her rotating face in a virtual gravity-free space, as if we could manipulate it ourselves, like any other malleable material. Wax is, once again, the key reference. In this metamorphosis, the asperities of the face, the cutaneous envelopes drilled with holes on the surface of our bodies then become caverns and other unknown territories.

The video-ludic experience is decisive, especially through the long sequence shots and uninterrupted tracking shots the artist decided to focus on. In other words, she focused on its cinematographically different spacio-temporal construction, making the four-angle screen and the monofocal perspective burst into pieces.

How can we consider the video game images beyond their recreational use, beyond the easy confusion one can make between reality and fiction, beyond the players, geeks and hackers’ position? Maybe, for example, as we look at physical self, by adopting a countergaming strategy, which questions the possibility of a video game with no game and no console, of a video game with no gameplay (Alexander R. Galloway, Gaming. Essays on Algorithmic Culture, Minneapolis-London: University of Minnesota Press, 2006). We are not far from the expanded cinema, which was enlarged not in the way that it produced elements beyond the classic cinema experience, but rather in the way that it could do without its constituent parts, without its filmic specificities. “This is not a particular style of filmmaking. [...] It is cinema expanded to the point at which the effect of film may be produced without the use of film at all.” (Sheldon Renan, Introduction to the American Underground Film 1967).

Regarding the video game, this means paying less attention to its recreational action and more to its representation space, less to the perception objects and more to the perception itself, or, paying better attention to the unique way in which they articulate perception, technology and imagination. This capacity to build hallucinated states, haunted by the spectres, as any other perception action would, is essential to video installations.

"Where I have broken or removed the first wall, the projected one remains. Since it is a projection nothing can pierce or eliminate it as long as the motors are running."

Adolfo Bioy Casares, The Invention of Morel 1940

As a whole, Laura Gozlan’s exhibition is filled with a narrative latency or, more specifically, with a length of time, with a time span lived away from the chronos. It appears intangibly in the white noise made out of sounds and voices forging linkage between the exhibition pieces as much as, in a more material way, in the screen sculptures and in the projection of refracted moving images. Dwelling in this chronotope — which evokes the dystopian ambiances found in science fiction, seizing a parallel time more than a time to come — is a significant challenge launched by physical self.

Riccardo Venturi, exhibition text